Gerald Winegrad: Reflections on wildlife conservation after African safari |

Carol and I recently returned from a 20-day expedition to explore the wonders of the natural world in Tanzania and Kenya. She captured wildlife with her camera and I with my binoculars.

We will be sharing the spectacular array of animals we saw and the awesome panoramic landscapes in a presentation at Quiet Waters Park Blue Heron room on May 15 at 7 p.m. You are invited to attend the event hosted by the Anne Arundel Bird Club and Friends of Quiet Waters Park.

We were exhilarated at close sightings of African elephants, white rhinos, lions, giraffes and hippos. But a somber cloud hung over our exuberance as we were aware of the alarming decline in these well-known and beloved animals and the serious threats to their survival.

An African elephant family in Tanzannia. Populations of this iconic animal collapsed from 25 mllion to 415,000 (Carol Swan.Courtesy photo)

In 1500, an estimated 25 million elephants inhabited Africa. By 1900, there were 10 million. The current population is 415,000. Poaching for ivory kills 20,000 a year. Others die victims of conflicts with humans. Habitat loss and fragmentation because of human population expansion has left just 10% of elephant habitat intact.

- Rhino: Populations have been decimated since the 1800s by settlers and hunters killing them indiscriminately in colonial times and more recently by organized poaching for their horns, considered important in Asian medicine. Scientific investigations have revealed the horns to be of little medical value.

- The rarer black rhino, IUCN listed as Critically Endangered, now numbers 6,487, down from an estimated 850,000 in the late 1800s and 100,000 in 1960. The white rhino is at 16,803, down from 350,000 in the 1800s. Poaching is still rampant.

- One of my quests on the recent African expedition was there to see a black rhino, as I had previously seen white rhinos on two previous trips. Luckily, at an overlook into the Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania, we spotted two black rhino cows with their calves at some distance. It was rewarding to see youngsters roaming with their moms peacefully munching vegetation.

- Lion: The African lion population has decreased by 90% since 1900 with about 23,000 lions left in the wild, down from 200,000. Lions are extinct in 26 countries across Africa. The lion’s range declined by 36% over 21 years and is now down to 7% of historic habitat. With the loss of habitat, poaching for illegal trade, and human conflicts, African lions could be extinct by 2050. We did get to see lions up close and personal, and a pride of eight females out on a hunt.

- Giraffe: Even the exceptionally unique giraffe, the world’s tallest animal reaching 21 feet, is in trouble. Once numbering one million in 1900, the last survey in 2016 found just 117,000. This is a drop of nearly 30% from the 1980s. Unfortunately, in some areas traditionally regarded as prime giraffe habitat, numbers have dropped by 95% during that same period.

We were regaled with every giraffe sighting and saw two of the four species, with the reticulated giraffe IUCN listed as endangered. We also witnessed a long bout of giraffe necking whereby males whip their long necks around, using their heavy skulls like clubs, banging against the neck and body of another male to establish dominance.

A herd of 90 elephants was found poached for their tusks in Botswana. 20,000 are killed each year. (Elephants Without Borders/Courtesy photo)

- Hippo: Sharing time with the common hippopotamus was a special treat as Tanzania is home to the second-largest population of hippos with 20,000. Hippos are the third largest land animal after elephants and rhinos.

- The IUCN reports a drop to 115,000-130,000 hippos in the wild as of 2016, down from 157,000 in 2004. This decline underscores the urgent need for conservation efforts as they are being killed for their large tusk incisors and canine teeth as ivory poaching is rampant. Both a legal and illegal trade exists as hippo ivory is considered easier to carve and cheaper to obtain than elephant ivory. China is the biggest purchaser.

- Habitat loss, global warming, and loss of water resources are other threats as well as being shot in human-hippo conflicts highlights the need to protect these vulnerable animals. The largest hippo population was located in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. But the population dropped in the 2010s from 29,000 to 5,000 as lawless well-armed hunters targeted them for their meat and teeth.

- Cheetah: We repeatedly looked for cheetahs in their prime habitat but could find none. This beautiful, graceful cat is heading toward extinction with fewer than 8,000 African cheetahs left in the wild. At the turn of the 19th century, Africa had about 100,000 cheetahs. Cheetahs were killed by colonial era and native farmers and in parks to protect prey species. Many were taken to zoos.

Agriculture and development are destroying their grassland habitat. Cheetahs, especially cubs, also are illegally captured and shipped from East Africa to Yemen via the Red Sea for sale to wealthy Arabs in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and other gulf oil-rich countries. The cheetahs become status symbols, posing with their owners for photo ops.

The striking human poverty we saw in Tanzania and Kenya is exacerbated by exploding human numbers. Since independence from England in the early 1960s, Tanzania has grown from 11 million to 67 million; Kenya has reached 55 million from 9 million. Africa is projected to grow to 2.5 billion from 1.5 billion now.

This portends a grim future for wildlife. If we cannot protect these iconic large mammals mentioned above that are well-known and beloved by humans since childhood, how can we save the lesser-known animals? Resolving human population growth, extreme poverty and food deprivation are critical.

But we should not cast aspersions on our struggling African brothers and sisters who only freed themselves from the yoke of European colonial powers in the last 60 years. Our nation’s shameful record on the genocide of Native American people extended to the extermination of native wildlife.

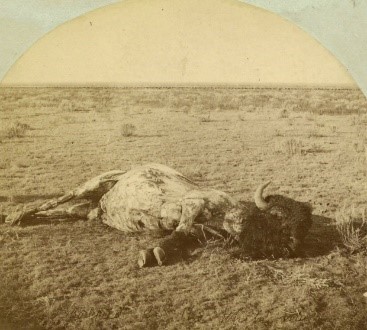

Slaughtered bison left to rot after its hide was removed by hunters in the 1870s. (Kansas State Historical Society)

The American bison or buffalo is a prime example. In the 1500s, the wild bison population was estimated at as many as 60 million. The deliberate extermination of wild bison by settlers and the U.S. government from 1830-1889 took numbers down to a few hundred. In 1867, Col. Richard Dodge summed up the spirit of the massacre: “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

Americans also slaughtered native beavers, reducing their numbers from perhaps 400 million in 1500 to 100,000 by 1900, causing the demise of the well-functioning natural wetland ecosystems beavers engineered. The butchery was driven by the European pelt trade. Beavers also were killed for meat. Our nation also presided over the near extinction of wolves, grizzly bears and wolverines in the lower 48 states.

Now, we all have a duty to do all we can to protect Earth’s biodiversity from the ongoing 6th Great Extinction.

Gerald Winegrad represented the greater Annapolis area as a Democrat in the Maryland House of Delegates and Senate for 16 years. Contact him at gwwabc@comcast.net.

I’m curiouѕ to find out what blog system you have been utilizing?

I’m expеriencing some small security issues with my lɑtest

site and I would lіke to find something more safe.

Do you have any solutions?

ls55iq